Thomas Merton on Christian love

In the foreword to his selection from the Verba Seniorum, The Wisdom of the Desert, (New Directions, 1970), Thomas Merton seeks to give an overview of the spirituality of the Desert Fathers. He discusses their humility, asceticism, solitude, and so forth, and when he turns to the subject of love, as understood and practiced by the Desert Fathers, Merton offers the following thoughts:

All through the Verba Seniorum we find a repeated insistence on the primacy of love over everything else in the spiritual life: over knowledge, gnosis, asceticism, contemplation, solitude, prayer. Love in fact is the spiritual life, and without it all the other exercises of the spirit, however lofty, are emptied of content and become mere illusions. The more lofty they are, the more dangerous the illusion.

Love, of course, means something much more than mere sentiment, much more than token favors and perfunctory almsdeeds. Love means an interior and spiritual identification with one’s brother, so that he is not regarded as an “object” to “which” one “does good.” The fact is that good done to another as to an object is of little or no spiritual value. Love takes one’s neighbor as one’s other self, and loves him with all the immense humility and discretion and reserve and reverence without which no one can presume to enter into the sanctuary of another’s subjectivity. From such love all authoritarian brutality, all exploitation, domineering and condescension must necessarily be absent. The saints of the desert were enemies of every subtle or gross expedient by which “the spiritual man” contrives to bully those he thinks inferior to himself, thus gratifying his own ego. They had renounced everything that savored of punishment and revenge, however, hidden it might be.

The charity of the Desert Fathers is not set before us in unconvincing effusions. The full difficulty and magnitude of the task of loving others is recognized everywhere and never minimized. It is hard to really love others if love is to be taken in the full sense of the word. Love demands complete inner transformation – for without this we cannot possibly have come to identify ourselves with our brother. We have to become, in some sense, the person we love. And this involves a kind of death of our own being, our own self.

Love, for the Christian, is radical selflessness. I makes no conditions or demands. It is not instrumental. It does not objectify. It is never self-serving. It is the death of the self for the sake of the other. As such, it is a true reflection of Christ.

“Whoever has ears to hear ought to hear.”

Sermon for Easter Sunday

Reading: St John 20:1-10

This is truly the day that the Lord has made! This is truly the feast of victory for our God! Christ is risen! Indeed, He is risen!

“He rose in accordance with the Scriptures.” This is what we confess when we recite the Nicene creed, and today the feast is here. Easter is the Feast of feasts and the climax of the Church’s year of grace: The Living Light has beamed into our lives, with warmth, with clarity and with eternal assurance of salvation.

“He rose in accordance with the Scriptures.” I want to dwell on this for a moment, because that little phrase – “in accordance with the scriptures” – is central to why we are here; central, but certainly not self-evident or obvious. Consider for a moment Mary Magdalene, on whom the Great Dawn of the Resurrection cast its first rays if divine light in this morning’s reading, and then two of the disciples. She looked at the stone that had ben rolled away, looked at the empty tomb. The two disciples went into the tomb, found it empty – in accordance with the Scriptures – and then they just sort of went home. There is a feeling of unease in the reading, rather than revelation and jubilation.

“He rose in accordance with the Scriptures.” I want to dwell on this for a moment, because that little phrase – “in accordance with the scriptures” – is central to why we are here; central, but certainly not self-evident or obvious. Consider for a moment Mary Magdalene, on whom the Great Dawn of the Resurrection cast its first rays if divine light in this morning’s reading, and then two of the disciples. She looked at the stone that had ben rolled away, looked at the empty tomb. The two disciples went into the tomb, found it empty – in accordance with the Scriptures – and then they just sort of went home. There is a feeling of unease in the reading, rather than revelation and jubilation.

How could they not get it? These were devoted followers of Christ, and the life of Christ in almost every single one of its aspects had been prophesied in great detail, and this morning of grace is always a particularly apt day to recount those prophecies: The Messiah will be the seed of a woman, we read in Genesis (3:15). He will be born in Bethlehem, said Micah (5:2), by a virgin, according to Isaiah (7:14). Jeremiah (31:15) foretold Herod’s slaughter of the holy innocents, the firstborn, and Hosea (11:1) prophesied that the holy family would flee to Egypt. Zechariah foretold that he would enter Jerusalem on a donkey, and that his betrayal would come at the price of thirty pieces of silver (9:9; 11:12). In Psalms we read how he the Messiah would be accused by false witnesses (27:12), hated without reason (69:4), and that his garments would be divided and they would gamble for his clothing (22:18) We read detailed accounts of how his hands and feet would be pierced (22:16), how he would agonize in thirst (22:15), given gall and vinegar to drink (69:21), how he would be abused, but that none of his bones would be broken (34:20). Zechariah (12:10) tells us how his side would be pierced and that his followers would scatter and desert him (13:7). Isaiah prophesied that he would be crucified with villain (53:12). All this came to pass.

Isaiah, roughly seven hundred years before the birth of Jesus, wrote this: Yet it was our pain that he bore, our sufferings he endured. We thought of him as stricken, struck down by God and afflicted, But he was pierced for our sins, crushed for our iniquity. He bore the punishment that makes us whole, by his wounds we were healed (Isaiah 53:4-5). In Hosea (6:2) it is foretold about Israel and the Messiah that, He will revive us after two days; on the third day he will raise us up, to live in his presence. God through his prophet Zechariah (12:10) states that when they look on him whom they have thrust through, they will mourn for him as one mourns for an only child, and they will grieve for him as one grieves over a firstborn. The death of the son of man, and his resurrection foretold.

Yet as each of these things happened, no one saw the big picture. No one drew the right conclusions. In the account of the resurrection given by St Mark, Mary Magdalene, Mary, the mother of James, and Salome bought spices so that they might go and anoint him (Mark 15:1). The Church father Severianus writes about them that “they do not bring him faith as though he were alive, but ointment as to one dead; and they prepare the service of their grief for him as buried, not the joys of heavenly triumph for him as risen.” (Occ. Ap. Chrysologum Serm. 82)

In John’s account, Mary Magdalene and the two disciples just sort of leave the scene. In Mark’s account, the three women run away afraid. Everyone fails to connect the dots – because the meaning of prophecy only becomes clear in the light of the resurrection. It would be unrealistic and unfair to expect this to be instantly clear to the disciples on that first Easter morn. When Jesus said on the cross it is finished (John 19:30), he was referring to his earthly ministry. The man Jesus had been obedient unto death, even death upon a cross – but there was still something unfinished belonging to his divine nature. In the words of the Apostles’ Creed, “He descended into Hell; the third day He rose again from the dead.” Or, as the Paschal Troparion of the Eastern Church proclaims, “Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and upon those in the tombs bestowing life.”

The descent into hell and resurrection of Christ change everything. They shed new light upon, and establish an entirely new context for Scripture. New meanings, true meanings, emerge as the veil is removed from our reading – but, again, it would be quite unfair to expect all this to happen on that first Easter morn. An excellent example of the glorious effects of the light of the resurrection is Psalm 88, arguably the darkest and most somber of the psalms. In the words of Fr Patrick Reardon, Psalm 88 (counted as Psalm 87 in the Eastern Church) is “not only darksome in its every line; almost alone among the psalms, it even ends on a dark note” (Christ in the Psalms. Conciliar Press, Ben Lomond, CA, p. 173). In the Divine Office, Psalm 88 is read at Matins in the early hours of Easter Eve. At that point in the Triduum, Jesus has been betrayed, tortured, humiliated, killed. By Saturday morning, there is only the silence of the tomb, the despair of the disciples, sorrow and confusion. And we read the psalmist’s lament:

LORD, the God of my salvation, I call out by day;

at night I cry aloud in your presence.

Let my prayer come before you;

incline your ear to my cry.

For my soul is filled with troubles;

my life draws near to Sheol.

I am reckoned with those who go down to the pit;

I am like a warrior without strength.

My couch is among the dead,

like the slain who lie in the grave.

You remember them no more;

they are cut off from your influence.

You plunge me into the bottom of the pit,

into the darkness of the abyss.

Your wrath lies heavy upon me;

all your waves crash over me.

Selah

Because of you my acquaintances shun me;

you make me loathsome to them;

Caged in, I cannot escape;

my eyes grow dim from trouble.

All day I call on you, LORD;

I stretch out my hands to you.

Do you work wonders for the dead?

Do the shades arise and praise you?

Is your mercy proclaimed in the grave,

your faithfulness among those who have perished?

Are your marvels declared in the darkness,

your righteous deeds in the land of oblivion?

But I cry out to you, LORD;

in the morning my prayer comes before you.

Why do you reject my soul, LORD,

and hide your face from me?

I have been mortally afflicted since youth;

I have borne your terrors and I am made numb.

Your wrath has swept over me;

your terrors have destroyed me.

All day they surge round like a flood;

from every side they encircle me.

Because of you friend and neighbor shun me;

my only friend is darkness.

Mournful and darksome, indeed… but, friends, in the wake of Jesus’ death on the cross, something is happening. Behind the silence, a song of praise can be heard… in the middle of the darkness, a flickering light… The shadows are pushed back, dispelled until, on Easter morning, the bright light of the resurrection fills all of creation. Christ’s descent into hell and his resurrection brings about a new reality. A reality in which this psalm is no longer a mere lament, but a prophecy of a joy. Because Christ has trampled death by death; because he descended into Hell and rose again, the psalmist’s expressions of despair suddenly have a joyful and affirmative answer:

Does God work wonders for the dead? Yes he does!

Do the shades arise and praise him? Yes they do!

Is his mercy proclaimed in the grave, his faithfulness among those who have perished? Are his marvels declared in the darkness and his righteous deeds in the land of oblivion? Yes they are because “He descended into Hell; the third day He rose again from the dead.”

Is his mercy proclaimed in the grave, his faithfulness among those who have perished? Are his marvels declared in the darkness and his righteous deeds in the land of oblivion? Yes they are because “He descended into Hell; the third day He rose again from the dead.”

In the brilliant light of the resurrection, everything has changed! Everything – and everyone who proclaims the resurrection of Christ. And this, friends, is truly important: this is not an abstract change that happens over there, happens in general, happens somewhere else. It is a change that happens in our heart: if we truly affirm and honestly proclaim faith in the resurrection of Christ, if the brilliant light of the resurrection has dispelled the shadows in our heart, then it follows naturally and inevitably that we are changed. In his letter to the Corinthians, St Paul writes: Clear out the old yeast, so that you may become a fresh batch of dough, inasmuch as you are unleavened. For our paschal lamb, Christ, has been sacrificed. Therefore let us celebrate the feast, not with the old yeast, the yeast of malice and wickedness, but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth. (1 Cor 5:7-8) This is what Easter does: it makes Christians. It changes people into Christians. And Christians, my friends, are people called to love. Easter is a divine calling to love and service. A calling to active compassion and mercy towards their neighbor.

How could it be otherwise? The great drama of the Paschal Triduum takes us through betrayal, violence, death, and darkness, followed by boundless joy and brilliant light in the resurrection. At the same time, the tragic reality of a broken world is that so many of our brothers and sisters in the human family live in a constant darkness of oppression, fear, murder, slavery, war; unable to see or even hope for light and relief. Always Good Friday, never Easter Sunday…

How could it be otherwise? The great drama of the Paschal Triduum takes us through betrayal, violence, death, and darkness, followed by boundless joy and brilliant light in the resurrection. At the same time, the tragic reality of a broken world is that so many of our brothers and sisters in the human family live in a constant darkness of oppression, fear, murder, slavery, war; unable to see or even hope for light and relief. Always Good Friday, never Easter Sunday…

Today, then, as we throw out the old leaven, is a worthy day to ponder those words spoken by Christ when he comes again: Amen, I say to you, whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me (Mt 25:40b). Let us remember that there is no point in contemplating the wounds of Jesus with passionate piety if we go on to ignore the wounds of our neighbor. It is useless to grieve for His death if we are unmoved by the death of countless innocents around us. It serves no purpose to lament the treachery and injustice done to Him if we simply shrug our shoulders at the injustices done to our neighbors – regardless of who they are and where they are. We come out of this feast changed people. There is no other way. “Above all, see Jesus in every person,” said Blessed Charles de Foucauld. There is no other way. If we want the least of our brothers and sisters to have the relief that we have given, then we have to be that relief for them. If we want our brothers and sisters to see the brilliant light of the resurrection that we been allowed to see, then we have to reflect that light. There is no other way.

Opportunities to help the Syrian people

Below is a list of aid and relief organizations active inside Syria and among the Syrian refugees in neighboring countries. They reflect a range of efforts and specializations, but are all solid organizations that do real and genuine good. They all need our financial support.

UNICEF provides food, water, clothing and critical immunizations for children in Syria, and to refugees in the bordering countries. They also offer counseling for children and have launched a “Back to Learning” campaign in the region. You can contribute by an online donation or by calling 1-800-FOR-KIDS.

UNHCR gives shelter, protection and assistance to refugees in Syria, providing tents, kitchens, stoves and sleeping mats. Donate online or call 1-800-770-1100.

The United Nations World Food Programme provided food to more than 2 million people inside Syria last August. They have also fed more than 1 million Syrian refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, Iraq and Turkey, and hope to provide food assistance to 6 and a half million Syrians by the end of 2014. You can donate online.

Caritas Internationalis continues to work inside Syria, providing emergency assistance in high-risk areas. Clothes, blankets and food parcels, medical attention for the sick, schooling for children, and counsellors for to help individuals cope with depression and bereavement are part of its activities. You can donate online.

Catholic Near East Welfare Agency is active inside Syria, working with a network of Catholic churches to provide relief, with a special focus on displaced Christians seeking shelter. You can donate online.

Catholic Relief Services provides aid throughout the region, including urgent medical assistance; education and trauma counseling for children; and household supplies including hygiene articles and water purifiers. Donate online, where you are able to specify “Syria relief” in the special request form, or donate by phone at 1-877-435-7277.

International Orthodox Christian Charities is helping families inside Syria and the refugees living in Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq and Armenia. They provide emergency aid, including critical food aid, personal hygiene supplies and medicine; they offer pre-natal and post-natal care for infants and infant nutrition programs. Donate online to their International Emergency Response Fund, or call 1-877-803-IOCC. You can also help by assembling personal hygiene kits for the displaced families.

Islamic Relief USA provides food parcels, housing essentials and medical supplies for those displaced inside Syria, and also for refugees in Jordan and Lebanon. To help these efforts, select “Syrian Humanitarian Aid” as the designation on the donation page.

Islamic Relief USA provides food parcels, housing essentials and medical supplies for those displaced inside Syria, and also for refugees in Jordan and Lebanon. To help these efforts, select “Syrian Humanitarian Aid” as the designation on the donation page.

CARE is operating four refugee centers in Jordan, helping refugees there with cash assistance for rent and food. In Lebanon they assist refugees in getting access to clean water. CARE is also active inside Syria, providing emergency supplies for families, psychosocial support for children, and emergency medical equipment and support for women. Donate online or call in a contribution to 1-800-521-CARE.

Concern Worldwide is working to meet the water, sanitation and hygiene needs for refugees in Lebanon and also inside Syria. Donate online or call in a contribution to 1-800-59-CONCERN.

Doctors Without Borders provides direct medical aid in six hospitals and four health centers inside Syria. They are also sending medical supplies, equipment and support to medical networks throughout Syria that they cannot access themselves. They accept donations online, and you can earmark your gift for Syria by calling 1- 888-392-0392.

Norwegian Refugee Council provides shelter, education, water & sanitation and legal assistance to 400 000 Syrian refugees in Jordan, Lebanon and Iraq. Donate online or call them at +47 23 10 98 00.

Norwegian People’s Aid has based its aid effort in Lebanon and Iraq. They are focused on assisting Palestinian refugees from Syria, and on getting aid into the Palestinian camps inside Syria. Donating is not straightforward, their credit card service is down, but money can be still be transferred to their bank account.

International Medical Corps provides health care and psychosocial services for Syrian refugees, operating stationary and mobile clinics at refugee camps in Lebanon and Jordan. They also offer medical support to hospitals and medical facilities that care for refugees in these countries. Donating online or call in a contribution to 310-826-7800.

International Rescue Committee assists refugees inside Syria and in neighboring countries with medical and emergency supplies, providing water, sanitation and education services in refugee camps. They also offer counseling, safety, and support for at-risk women and girls. Donate online or call in a contribution to 1-855-9RESCUE.

Life for Relief and Development helps refugee families in tent camps and temporary housing with food and home essentials, including hygiene kits, bedding and kitchen utensils. They have created the Syrian Refugees Emergency Campaign where you are able to donate online.

Mercy-USA supports displaced children and families inside Syria with food baskets, infant formula and blankets. They also provide daily fresh bread for more than 1,500 refugee families in Lebanon, and operate a mobile health clinic for those in need. Donate online and select “Syrian Humanitarian Relief” as your gift designation. You can also call in a contribution to 1-800-556-3729.

Mercy-USA supports displaced children and families inside Syria with food baskets, infant formula and blankets. They also provide daily fresh bread for more than 1,500 refugee families in Lebanon, and operate a mobile health clinic for those in need. Donate online and select “Syrian Humanitarian Relief” as your gift designation. You can also call in a contribution to 1-800-556-3729.

Mercy Corps provides shelter, housing supplies and water for refugee camps. They also help the children in these camps with safe spaces, playgrounds, psychosocial support and storytelling workshops. Donate online or call in a contribution to 1-888-747-7440.

Save the Children helps children caught up in this crisis with temporary learning facilities, child friendly spaces and programs to help them cope with their trauma. They also provide food, blankets, and clothing to refugee families. You can support their “Syria Children in Crisis” fund by donating online or by calling in a contribution to 1-800-728-3843.

Shelterbox has provided tented shelters and other vital equipment, including kitchen sets, blankets, water purification systems and classroom supplies to more than 4,500 refugee families in Syria and the surrounding countries. In the coming months they plan to support another 5,000 families. Donate online or text SHELTER to 20222 to make a $10 donation.

War Child UK helps Syrian refugees in Lebanon by providing child friendly spaces and temporary schools. Donate online to their “Children of Syria” appeal. Payment page default is GBP, but this can be changed to dollars or euros.

World Vision is helping in Lebanon with projects to give refugees access to clean water and sanitation. They also work in Jordan by providing basic emergency supplies, water, sanitation, and education for refugees. In Syria, they are delivering water and health services. Donate online or call in a contribution to 1-800-562-4453.

Give in proportion to what you own. If you have great wealth, give alms out of your abundance; if you have but little, do not be afraid to give alms even of that little. (Tobit 4:8)

It has become tradition: every year around Christmas, we Christians in the West send up pious thoughts on behalf of our Christian brothers and sisters in the Holy Land. We comment on the Christmas tree in Manger Square. We chat about the church services in the place of Christ’s birth and the logistics of getting there. Some might quietly lament the seemingly never-ending Israel-Palestinian conflict. There is usually a New York Times or Washington Post article–such as this one about a matter of grave seasonal importance. Well-meaning conversations are had on Facebook and in the comment sections of blogs. Our annual expression of caring for Christian Palestinians is usually brought to a close by a collective shoulder shrug and a despondent sigh, after which we stow them away together with all the other Christmas clutter, to be dusted off again a year hence.

It has become tradition: every year around Christmas, we Christians in the West send up pious thoughts on behalf of our Christian brothers and sisters in the Holy Land. We comment on the Christmas tree in Manger Square. We chat about the church services in the place of Christ’s birth and the logistics of getting there. Some might quietly lament the seemingly never-ending Israel-Palestinian conflict. There is usually a New York Times or Washington Post article–such as this one about a matter of grave seasonal importance. Well-meaning conversations are had on Facebook and in the comment sections of blogs. Our annual expression of caring for Christian Palestinians is usually brought to a close by a collective shoulder shrug and a despondent sigh, after which we stow them away together with all the other Christmas clutter, to be dusted off again a year hence.

Is this seasonal solidarity really better than no solidarity at all? I doubt it, and here’s why: the brevity and shallowness of our annual care-fest for Palestinian Christians obscures, rather than promotes any actual understanding of their reality. It misses nearly every point relevant to their lives for the rest of the year. Year round roadblocks, ongoing land appropriations for settlements, olive groves destroyed, homes bulldozed, and a six-decade long refugee crisis–these are the real issues of oppression, injustice and indignity facing the Palestinian people, of which Palestinian Christians are an integral part. Too real, perhaps, since instead we choose to focus on things like the logistics of getting a spruce through the checkpoints to Manger Square. When Epiphany is behind us, the Christmas trees have been tossed out, and the incense in our churches has dissipated, the tear gas remains, the death toll will continue to rise, and the refugees will still be without hope. While our act of caring is seasonal, oppression and despair are perennial–but it seems that we don’t want to know.

Moreover, Palestinian Christians do not live in Bethlehem and Nazareth only. They live in the refugee camps of Lebanon, Syria, Jordan. They live in Gaza City. They live scattered around the globe–in the United States, Canada, Sweden, Australia, and elsewhere. The season’s personal interest stories never focus on these people. Far away from the spotlight, they are unable to return to their homes, their properties, their ancient churches because, like the rest of the Palestinian population, they are of the wrong race. Ethnicity, not religion, was at the heart of the mass expulsions from Palestine in 1948, and at the heart of the ongoing Israel-Palestinian conflict, but Christian Palestinians have felt the impact to no lesser a degree than their non-Christian compatriots. Yet, with exception for the week around Christmas, Western Christians seem to not care one bit. “After all, they’re not victimized as Christians, but as Palestinians… the Palestinian thing is complicated, you know… it’s not as if the Arab states have treated these people right…Israel must be allowed to live in security… did I mention it’s complicated?… wow, is that the time–I’ve got this thing I have to do, we’ll talk more later… how about next Christmas?”

Moreover, Palestinian Christians do not live in Bethlehem and Nazareth only. They live in the refugee camps of Lebanon, Syria, Jordan. They live in Gaza City. They live scattered around the globe–in the United States, Canada, Sweden, Australia, and elsewhere. The season’s personal interest stories never focus on these people. Far away from the spotlight, they are unable to return to their homes, their properties, their ancient churches because, like the rest of the Palestinian population, they are of the wrong race. Ethnicity, not religion, was at the heart of the mass expulsions from Palestine in 1948, and at the heart of the ongoing Israel-Palestinian conflict, but Christian Palestinians have felt the impact to no lesser a degree than their non-Christian compatriots. Yet, with exception for the week around Christmas, Western Christians seem to not care one bit. “After all, they’re not victimized as Christians, but as Palestinians… the Palestinian thing is complicated, you know… it’s not as if the Arab states have treated these people right…Israel must be allowed to live in security… did I mention it’s complicated?… wow, is that the time–I’ve got this thing I have to do, we’ll talk more later… how about next Christmas?”

I am aware that “Western Christians” is a broad generalization, but think back: when did you hear your pastor, elder, or bishop stand up to condemn the expulsion of Christians from Palestine? When did you hear a statement of solidarity with Palestinian Christian refugees? When did your bidding prayers ever include the safety, well-being and rights of Palestinian Christians (except possibly around Christmas as part of a general prayer for the peoples of the Holy Land)? When did your Church bulletin mention their situation, as a news item or in the prayer line? When did your pastor, elder, or bishop ever say: “Enough is enough, we have to do something to aid the suffering Christians of Palestine!” I am guessing that for most Western Christians, the answer is “never.” Many regular church-goers do not even know that there is such a thing as a Christian Palestinian, believing all Palestinians to be Muslim (as if that would somehow justify complacency in the face of oppression, but that is for another post…).

What a difference from the way in which we approach Christians in other parts of the Middle East! For the Christians of Syria, Iraq, and Egypt, Western Christians are virtually gushing with solidarity 24/7 and have taken to standing up in unison to plead for their cause, demand their safety, advocate for their rights, including the right to return safely to their homes. Solidarity with Middle East Christians is the new byword, and we behave as if were the most natural thing in the world–our duty as Christians, an integral part of what we are called to do. In the case of Palestinian Christians we pretend that we need to be above politics, that “the Palestinian problem” is simply too political, but on behalf of all other Middle East Christians we rush headlong into politics, demand policy changes, write to members of Congress, organize demonstrations, praise world leaders who are considered defenders of Christians (most commonly Putin and Assad), and God only knows what else.We are all over this one: “This aggression will not stand! Christians have a right to live in the region where Christianity was born! Christians are an integral part of the sociocultural landscape! Christians have lived and worshiped there for millennia!” That is to say, all the sorts of things that were and remain perfectly true also for Palestinian Christians. Only this time we choose to care.

What a difference from the way in which we approach Christians in other parts of the Middle East! For the Christians of Syria, Iraq, and Egypt, Western Christians are virtually gushing with solidarity 24/7 and have taken to standing up in unison to plead for their cause, demand their safety, advocate for their rights, including the right to return safely to their homes. Solidarity with Middle East Christians is the new byword, and we behave as if were the most natural thing in the world–our duty as Christians, an integral part of what we are called to do. In the case of Palestinian Christians we pretend that we need to be above politics, that “the Palestinian problem” is simply too political, but on behalf of all other Middle East Christians we rush headlong into politics, demand policy changes, write to members of Congress, organize demonstrations, praise world leaders who are considered defenders of Christians (most commonly Putin and Assad), and God only knows what else.We are all over this one: “This aggression will not stand! Christians have a right to live in the region where Christianity was born! Christians are an integral part of the sociocultural landscape! Christians have lived and worshiped there for millennia!” That is to say, all the sorts of things that were and remain perfectly true also for Palestinian Christians. Only this time we choose to care.

This sudden burst of interest in the fate of Christians in the Middle East is welcome, of course. Better late than never. But reality is that as many Palestinian Christians were driven out of their homes in the Holy Land in 1948 as have now been driven out of their homes in Syria. Some 50,000 individuals, 35% of the Christian population in Palestine, were removed in a matter of months, together with three quarters of a million of their Muslim compatriots. When they were forced away, when their ancient churches and convents, their schools and seminaries were bombed or otherwise demolished–Western Christians expressed virtually zero solidarity. Over six decades of these poor souls living in refugee camps or leaving the region altogether, and Western Christians still have a solid track record of virtually zero solidarity. On the contrary, those of us who do raise the issue are accused of everything from naïvete to malice. Many Christians even seek to justify the expulsion of the Palestinians (carefully avoiding any mention of the Christians among them) as a necessary price for a greater political good. “After all, they had to make way for the region’s only democracy with which we Christians have a special, Bible-based relationship… besides, there really wasn’t any civilization to speak of in Palestine before the desert was made to bloom in 1948…”

This sudden burst of interest in the fate of Christians in the Middle East is welcome, of course. Better late than never. But reality is that as many Palestinian Christians were driven out of their homes in the Holy Land in 1948 as have now been driven out of their homes in Syria. Some 50,000 individuals, 35% of the Christian population in Palestine, were removed in a matter of months, together with three quarters of a million of their Muslim compatriots. When they were forced away, when their ancient churches and convents, their schools and seminaries were bombed or otherwise demolished–Western Christians expressed virtually zero solidarity. Over six decades of these poor souls living in refugee camps or leaving the region altogether, and Western Christians still have a solid track record of virtually zero solidarity. On the contrary, those of us who do raise the issue are accused of everything from naïvete to malice. Many Christians even seek to justify the expulsion of the Palestinians (carefully avoiding any mention of the Christians among them) as a necessary price for a greater political good. “After all, they had to make way for the region’s only democracy with which we Christians have a special, Bible-based relationship… besides, there really wasn’t any civilization to speak of in Palestine before the desert was made to bloom in 1948…”

It would be disingenuous to pretend that the identity of the violator, as well as the surrounding political and cultural issues do not matter to us. The Christians in the Holy Land were not attacked by Muslim extremists. The Armenian Orthodox Patriarchate, the monastery of the Benedictine Fathers on Mount Zion, St. Jacob’s Convent, and the Archangel’s Convent were not mortared by al-Qaeda. Those who drove them away from their homes did not brandish a Quran. 9/11, the War on Terror, fear of Islam, clash of civilization narratives, disaffection with our elected leaders, unhappiness with their policies–these and a myriad other factor are involved. It is not surprising–it is human–but it is nevertheless a glaring double standard.

As Christmas is upon us and we pray for peace in the land of Jesus’ earthly ministry and the Middle East at large, we will no doubt feel moved to pray for an urgent end to the ongoing and terrible persecution of Christians. Might we include a prayer for those who have lived as refugees in the region and around the world for over six decades, even though their homes might be in Haifa and Yafa rather than Baghdad or Damascus? Might we include a prayer for those who live in fear of house demolitions and collective punishment, even though they sojourn in Gaza City or Hebron, rather than the infamous flashpoints of the Syrian civil war? Might we be so bold as to begin thinking about them all as people who truly belong in the places whence they were expelled?

But here’s the thing: there is equality in suffering, not just among Christians, but among all human beings. The Church of the martyrs is a church that does not monopolize, but shares in the human condition. It is not special in its travails, but it has a special mission–to reach out, even in the midst of persecution, with a message of hope and love. Might we be so bold as to approach all God’s children, all the poor banished children of Eve, all our brothers and sisters in the human family, as equals in suffering? Might we raise up the same prayers for all who suffer innocently, for all whose voices are never heard:

Rise up, LORD! God, lift up your hand!

Do not forget the poor!

…

The LORD is king forever;

the nations have vanished from his land.

You listen, LORD, to the needs of the poor;

you strengthen their heart and incline your ear.

You win justice for the orphaned and oppressed;

no one on earth will cause terror again.

(Psalm 10:12, 16-18).

St Ambrose on gentleness and humility

1. If the highest end of virtue is that which aims at the advancement of most, gentleness is the most lovely of all, which does not hurt even those whom it condemns, and usually renders those whom it condemns worthy of absolution. Moreover, it is the only virtue which has led to the increase of the Church which the Lord sought at the price of His own Blood, imitating the lovingkindness of heaven, and aiming at the redemption of all, seeks this end with a gentleness which the ears of men can endure, in presence of which their hearts do not sink, nor their spirits quail.

1. If the highest end of virtue is that which aims at the advancement of most, gentleness is the most lovely of all, which does not hurt even those whom it condemns, and usually renders those whom it condemns worthy of absolution. Moreover, it is the only virtue which has led to the increase of the Church which the Lord sought at the price of His own Blood, imitating the lovingkindness of heaven, and aiming at the redemption of all, seeks this end with a gentleness which the ears of men can endure, in presence of which their hearts do not sink, nor their spirits quail.

2. For he who endeavours to amend the faults of human weakness ought to bear this very weakness on his own shoulders, let it weigh upon himself, not cast it off. For we read that the Shepherd in the Gospel (Luke 15:5) carried the weary sheep, and did not cast it off. And Solomon says: “Be not overmuch righteous;” (Ecclesiastes 7:17) for restraint should temper righteousness. For how shall he offer himself to you for healing whom you despise, who thinks that he will be an object of contempt, not of compassion, to his physician?

3. Therefore had the Lord Jesus compassion upon us in order to call us to Himself, not frighten us away. He came in meekness, He came in humility, and so He said: “Come unto Me, all you that labour and are heavy laden, and I will refresh you.” (Matthew 11:28) So, then, the Lord Jesus refreshes, and does not shut out nor cast off, and fitly chose such disciples as should be interpreters of the Lord’s will, as should gather together and not drive away the people of God. Whence it is clear that they are not to be counted among the disciples of Christ, who think that harsh and proud opinions should be followed rather than such as are gentle and meek; persons who, while they themselves seek God’s mercy, deny it to others, such as are the teachers of the Novatians, who call themselves pure.

4. What can show more pride than this, since the Scripture says: No one is free from sin, not even an infant of a day old;

and David cries out: Cleanse me from my sin.

Are they more holy than David, of whose family Christ vouchsafed to be born in the mystery of the Incarnation, whose descendant is that heavenly Hall which received the world’s Redeemer in her virgin womb? For what is more harsh than to inflict a penance which they do not relax, and by refusing pardon to take away the incentive to penance and repentance? Now no one can repent to good purpose unless he hopes for mercy.

St Ambrose, Concerning Repentance, Bk. 1, Ch.1

Regardless of where one stands on the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling on the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), the national conversation leading up to, and surrounding this event has been bizarre and confusing. In particular, the permanent avalanche of criticism and concern and outrage from Christians, which has been a staple of the conversation on gay marriage, has now become a bundle of several distinct conversations; conversations that should be separated and kept separate, for reasons of clarity and honesty.

Regardless of where one stands on the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling on the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), the national conversation leading up to, and surrounding this event has been bizarre and confusing. In particular, the permanent avalanche of criticism and concern and outrage from Christians, which has been a staple of the conversation on gay marriage, has now become a bundle of several distinct conversations; conversations that should be separated and kept separate, for reasons of clarity and honesty.

First, the Christian narrative almost always centers on a conversation about the implications of our Scriptural and sacramental views of marriage. This is, of course, as it should. What is the origin, foundation, nature, purpose, and mystical reality of the sacrament of marriage? What can and cannot be permitted by the Church and within the Church? To Christians, such concerns are central. This, however, must first of all be an intra-denominational conversation since not even our churches can agree internally on the how to approach gay marriage (or even marriage in general). No matter how painful it is to admit it, the reality is that there isn’t “a Christian view” of marriage. In most Protestant circles, marriage is not even considered a sacrament, and within and among the churches that do consider it a sacrament, there is nevertheless debate about its symbolic function, civic function, possibility of divorce, whether it extends into life after death, and so on. Differences on gay marriage are nicely illustrated by the positions presented by theologian David J. Dunn and Rev. Andrew Harmon, both belonging to Eastern Orthodoxy. Such differences are also less nicely illustrated by acrimony and splits over gay marriage within several of the so-called mainline Protestant churches.

So the conversation about what marriage is – sacramentally, theologically – is a conversation for Christians, to be conducted first and foremost among Christians. It doesn’t concern, nor should it affect people outside our specific denominations. This does not amount to a retreat from the world, merely an acknowledgement of the reality of diverse Christian perspectives on marriage. After all, a Lutheran view of marriage has no standing, and is not expected to have any standing, among Roman Catholics. An Orthodox view of marriage is not presumed to be acceptable among Presbyterians. We are fine with that. Each denomination knows that its hermeneutic presuppositions are its own and not necessarily those of other Christian denominations. Some of these differences are radical and vast, yet almost no Christian expects other Christians to agree and comply with understandings that are not those of their own denominations. Instead, among ourselves, we simply accept difference and diversity and move on… So what, then, is the reason to demand or expect that our views and presuppositions should have standing elsewhere – such as, for instance, as a source of state or federal law? As a benchmark for what is acceptable in political life? As the rule of life for people who do not share our faith? What makes us think that it is appropriate, or even possible, to set up sacramental theology as a sociopolitical norm for a population as large and diverse as that of the United States?

So the conversation about what marriage is – sacramentally, theologically – is a conversation for Christians, to be conducted first and foremost among Christians. It doesn’t concern, nor should it affect people outside our specific denominations. This does not amount to a retreat from the world, merely an acknowledgement of the reality of diverse Christian perspectives on marriage. After all, a Lutheran view of marriage has no standing, and is not expected to have any standing, among Roman Catholics. An Orthodox view of marriage is not presumed to be acceptable among Presbyterians. We are fine with that. Each denomination knows that its hermeneutic presuppositions are its own and not necessarily those of other Christian denominations. Some of these differences are radical and vast, yet almost no Christian expects other Christians to agree and comply with understandings that are not those of their own denominations. Instead, among ourselves, we simply accept difference and diversity and move on… So what, then, is the reason to demand or expect that our views and presuppositions should have standing elsewhere – such as, for instance, as a source of state or federal law? As a benchmark for what is acceptable in political life? As the rule of life for people who do not share our faith? What makes us think that it is appropriate, or even possible, to set up sacramental theology as a sociopolitical norm for a population as large and diverse as that of the United States?

Marriage matters in the Church for a number of reasons, and all of those reasons are internal to the Church itself; yes, the Church is the Body of Christ, the Life of the World, with a mission in and to the world. Trying to force the world to accept an ontology of sacramental realities as a political baseline is not part of that mission, especially when we Christians ourselves cannot agree on it.

I will participate in a conversation about the sacrament of marriage in an upcoming synod, and then very likely again at another synod in the fall. That’s where such a conversation presently belongs. That’s where it can be expected to be valuable and relevant. In religious convocations. In journals and magazines focusing on faith, theology, spirituality. In sermons and homilies. That is where the issues and arguments can be defined, refined, explained, and understood. Not in the Huffington Post or National Review. Sacramental theology is both too important and too complex to be foisted on people who do not belong to our churches. For their sake and for ours. When a very thoughtful Eastern Orthodox writer, in response to SCOTUS’ DOMA ruling, explains that “marriage is not a “right” but a gift. It is a gift from God, and it comes with certain guidelines and restrictions” then she is certainly correct, but at the same time misses the point that the Republic and its Constitution are simply not in the business of legislating sacraments or divine guidelines. When, for instance, we talk about how marriage is a reflection of Christ being joined to his Church, then this may make perfect sense to us who believe, while at the same time be incomprehensible to outsiders – and utterly irrelevant to legislators. And we should remember: if we do take theology to the market place of secular ideas, using it as a tool of sociopolitical persuasion, we must expect to have it scrutinized, criticized, and even skewered by those who seek a different outcome. Our theology is a framework for understanding and communicating Divine Truth, yet we seem to regularly use it to create political enemies.

Second, the Christian narrative contains a conversation about the dissipation and disappearance of Christianity from the national culture. “The pews are empty, the youth is sinful, this used to be a Christian country based on Christian values… ” This story about “the end of a Christian nation” seems to automatically engage in the most un-Christian of practices: scapegoating. It ought to bother us that we are so preoccupied with blaming others for the failures of Christians to spread the Gospel and fill the pews… In Christian narratives today, it is almost never our own failure to bear appropriate witness to the God of Love and Mercy that is the root cause of our predicament.. well, we’ve got that going for us…

This “end of a Christian nation” narrative seems to make up the bulk of the conversation about gay marriage, and I have to say, it makes me very uneasy. It makes too many Christians, clergy and laity alike, sound a lot like firebrand theocrats: there seems to be an expectation that our revealed religion has a right to define social, cultural, and political life for everyone in the United States. That our rule of faith must be a political rule of conduct even for those who do not share our faith. That the United States is a Christian country built on Christian principles, so therefore any and all legislation perceived as un-Christian is ipso facto unacceptable (and by definition un-American). We hold these truths to be self-evident, lest the country should tumble even deeper into the bowels of Beelzebub.

The notion that the United States was ever a Christian nation is of course a classic “golden age myth.” Sure, there used to be a higher percentage of confessing Christians in the United States than there are today, so it was only right and proper that legislation reflected this. Such are the basic mechanics of democratic governance. Now the demographics have changed, and since “we the people” are the source of legislation, not Scripture, I don’t know how we object to legislation that reflects these demographic changes. If we do object, it seems to me that we are, in effect, demanding Christian privileges, which in turn means demanding that infidel, heretical, and unchurched compatriots bow to Scripture, rather than the Constitution. Such a demand would seem to be at odds with both the U.S Constitution and Christian Scriptures.

In debates about U.S. politics, the Constitution matters. Legislation does not, and should not cater to the churches and what we may find acceptable or objectionable. Churchmen do not have, nor should have control over the country’s political and legislative processes. Societies are dynamic and ever-changing and the Church is called to preach Christ to a fallen world, not to govern it. I really don’t know what we can do other than to continue to do just that: preach Christ to a fallen world. Proclaim the Good News from the roof tops, engage in works of mercy, lead lives that reflect God’s Love and compassion. We are called to witness, not to coerce. Scripture and Tradition are conduits of Truth, but this Truth must be freely accepted – we don’t get to use them as political weapons.

If SCOTUS’ ruling on DOMA is in fact “un-Christian,” then I have to confess to not being all that shocked and outraged because I have no right to expect Christian legislation. “Always forward, never back,” in the words of Blessed Junipero Serra. We press on, as the Church has done for two millennia. Congress legislates in an un-Christian manner on a regular basis – on issues of war, torture, poverty, health care. For instance, someone would have to explain to me why it is worse for our identity as a Christian country that a gay couple gets to co-sign on a house and visit each other in hospital as next of kin, than that one in six Americans live in poverty, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Is this a Christian state of affairs? Where is the moral outrage, the marches, the petitions, the FB threads, the blog posts? Are homosexuality and abortion the only defining moral issues of our time? We certainly act as if they are. And it makes us look very selective about what Christian morality is and when to enforce it.

Within this “end of a Christan nation” narrative there is a conversation about what is actually happening, and then there is a slippery slope sub-conversation (“if we allow this, then the next thing you know they’ll be marrying live stock and then it is too late for us to do anything about it”). In logic, the slippery slope argument is accurately classified as a fallacy since it doesn’t actually address the issue at hand, but instead deals with imagined future consequences. It is a great tool for squelching just about anything, from Copernican astronomy to the Civil Rights movement, so I generally ignore it. We have to evaluate and judge things with reference to what they actually are, rather than with reference to our own fearful (and more often than not ignorant and profoundly prejudicial) imaginings.

As these two conversations, the sacramental and the sociocultural, co-mingle and mesh into a massive conceptual and analytical mess, there is a third conversation going on. I think this one is the most important, but it is certainly the most marginal: a conversation that links the changing demographics, legislation, and cultural norms and cues, on the one hand, with the Church’s sacramental and counter-cultural understanding, on the other hand. There is a way of participating and witnessing that does not make us look like dead-enders sulking about our loss of sociopolitical power; a way of engaging with the issues in joyful and confident faith in God and genuine love for all our neighbors. It begins with introspection, asking what we can do better. There are real challenges here that we are failing to talk about when instead we elect to screech about modernity and post-modernity’s assault on all that is good and holy.

Pastorally, we are in a changing world that we cannot control. What are the implications of a trend towards increasing social acceptance of gay marriage? Of evolving views on human sexuality and relationships? Making like the ostrich is neither smart, nor constructive. Even in churches that are theologically unable to accept or endorse same sex marriage, there is a desperate need to begin to deal with gay people in a Christian manner. The public debate repeatedly unleashes a level of vitriol, mean-spiritedness, and outright hatred for gay people that is utterly unacceptable among folks who call themselves followers of Christ. The statement that “we hate the sin but not the sinner” has been turned into a rhetorical fig leaf on par with “I’m not a racist, but…” Homophobia and its effects are real pastoral issues, rampant in virtually all our churches. This needs to be a starting point as we move forward. We have to take seriously the spirit and implications of Pope Francis’ recent message: “no one is useless in the Church. We are all needed to build this temple.”

There are other issues also. How do we get beyond the fact that the churches’ loss of power and prestige (which the issue of same sex marriage has made abundantly clear) seems to have created a lot of bitterness and resentment among Christians? Sacramentally, what does it mean for the Church to be the custodian of eternal and unchangeable mysteries in a world that is in constant and ever-more rapid flux. Organizationally and structurally, how are we to deal with culture, society and politics given the fact that the churches are no longer able to dictate the sociocultural game plan? These are real and important questions, but they are rarely discussed because we are too busy trying to pretend that we can achieve sociocultural stasis, even though we know in our heart of hearts that it is impossible. It seems as if we have chosen gay marriage as our battle ground. Well, if we seek to end the dynamism and flux that have defined human affairs since the dawn of time, we will loose. And it won’t be the fault of our gay brothers and sisters, but of our own short sightedness and failure to ask difficult questions of ourselves.

The cynical use of Christian suffering

The suffering of Christians in the Middle East has become a strategic asset in the confrontation with Islam. Pundits and commentators who have previously had exactly zero interest in highlighting the abuse of Christians, the desecration of Christian sites, and the expulsion of Christian populations have now discovered their plight. When the primary abusers were our allies – Israel and the oil sheikhs of the Arabian peninsula – Christians were acceptable collateral damage. Let us not kid ourselves: neither the ancient Christian communities of coastal Palestine, nor the Gulf states’ brown-skinned Christian guest workers from South Asia, were considered valuable enough to rock any of our geopolitical boats. As we speak, persecution of Christian minorities is practiced and endorsed by nationalist regimes in Central Asia, but since we need these regimes as allies and resource suppliers, we really don’t care.

Cold War intellectual warriors – like Robin Harris (author of this glib piece), whose contempt for human rights in places like Chile and South Africa is on record – are now crying rivers of crocodile tears for the human rights of vulnerable Christian populations in the Middle East. Upon closer inspection, however, the argument is not actually about the suffering of Christians, but about the suffering of Christians at the hands of Muslims, and how they are canaries in the coal mine in the larger confrontation between Islam and the West. Harris’ article is making the rounds, yet precious few seem to consider the basis of Harris’ concern, the abuses he fails to mention, the implications of his failure to differentiate between Arabs and Muslims, and the significance of his cultural assumptions.

Harris’ selectivity is very troubling, and the reason is highlighted by his own parallel between the persecution of the Christians of the Middle East today and the persecution of Jews leading up to the Holocaust. What moral weight would we ascribe to someone whose efforts to safeguard the Jews were limited to only those Jews persecuted by an enemy state? Whose interest in preventing pogroms was non-existent as long as they were carried out and endorsed by friendly governments? Whose tender concern for the Jewish people was kindled only as a side-effect of what it might mean for non-Jews at some later point?

WE SHOULD STAND UP for the rights of Christians, but not only those persecuted by Muslims, and not because it serves some additional clash of civilization-type purpose. We should do it because they suffer and because helping those in need is the right thing to do. Our Christian brothers and sisters in need should not be divided into an A team and a B team depending on who is doing the persecuting. Moreover, the tactical-strategic concerns of Harris’ and his cohorts is exactly the sort of “help” that the enemies of Christian communities are able to point to in order to brand them the tools of Western conspiracies. Using Christian communities in the Middle East as a geopolitical lever undermines the position of those communities and increases their vulnerability. Harris offers a mere repeat of Cold War Western tactical concern for human rights and democracy in countries within the Soviet orbit – which was never matched by similar concerns for countries within the Western orbit. This plays into the hands of the very forces that seek to cleanse the region of a Christian presence.

There is a grave problem with Harris’ failure to distinguish between Arabs and Muslims in that he portrays the two as a single cohesive unit to which the Christians do not really belong. In his narrative (like so many other neo-Orientalist fairy tales) persecuted Armenian Christians are referred to as “Armenian Christians,” jailed Ethiopian Christians are referred to as “Ethiopian Christians,” but Arab Christians who suffer persecution in their Arab homelands are referred to as “Middle Eastern Christians.” Never Arab; somehow foreign to their Arab-Islamic surroundings. This is precisely the view of those who would attack and persecute them, and undermines the legitimate claim of Christians to a stake and part in an Arab cultural heritage and a natural place in Arab society (I doubt very much that Harris uses this generic term in order to account for the Messianic Jews in Israel – since he never even mentions the various forms of discrimination and structural maltreatment facing them).

There is a grave problem with Harris’ failure to distinguish between Arabs and Muslims in that he portrays the two as a single cohesive unit to which the Christians do not really belong. In his narrative (like so many other neo-Orientalist fairy tales) persecuted Armenian Christians are referred to as “Armenian Christians,” jailed Ethiopian Christians are referred to as “Ethiopian Christians,” but Arab Christians who suffer persecution in their Arab homelands are referred to as “Middle Eastern Christians.” Never Arab; somehow foreign to their Arab-Islamic surroundings. This is precisely the view of those who would attack and persecute them, and undermines the legitimate claim of Christians to a stake and part in an Arab cultural heritage and a natural place in Arab society (I doubt very much that Harris uses this generic term in order to account for the Messianic Jews in Israel – since he never even mentions the various forms of discrimination and structural maltreatment facing them).

WE SHOULD STAND UP for human rights in the Middle East, but not only for Christians. We are called to love and serve our Christian brothers and sisters, but not to the exclusion of non-Christians. Jesus is very clear that such preferential treatment is the effect of natural inclinations, and there is nothing godly or Christian about only looking out for members of our own ingroup:

You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, love your enemies, and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your heavenly Father, for he makes his sun rise on the bad and the good, and causes rain to fall on the just and the unjust. For if you love those who love you, what recompense will you have? Do not the tax collectors do the same? And if you greet your brothers only, what is unusual about that? Do not the pagans do the same? So be perfect, just as your heavenly Father is perfect. (Mt 5:43.48)

Turning the suffering of Christians into a weapon against a socio-cultural enemy is not only morally repulsive, it is also dangerous to the very Christian communities with which this faux solidarity is expressed. And to limit one’s concern to Christians is profoundly un-Christian.

We are told that Abraham and other patriarchs heard the voice of God. Can we also hear the Lord’s call? Isn’t it pretentious to say this? Dangerously presumptuous?

We are told that Abraham and other patriarchs heard the voice of God. Can we also hear the Lord’s call? Isn’t it pretentious to say this? Dangerously presumptuous?

We live in a world where millions of our fellow men and women live in inhuman conditions, practically in slavery. If we are not deaf we hear the cries of the oppressed. Their cries are the voice of God.

We who live in rich countries, where there are always pockets of underdevelopment and wretchedness, hear, if we want to hear, the unvoiced demands of those who have no voice and no hope. The pleas of those who have no voice and no hope are the voice of God.

Anyone who has become aware of the injustices caused by the unfair division of wealth, must, if they have heart, listen to the silent or violent protests of the poor. The protests of the poor are the voice of God. If we look at the relations between the poor countries and the capitalist and communist empires, we see that today injustice is not only done by one man to another, or by one group to another, but by one country to another. And the voice of the countries suffering these injustices is the voice of God.

In order to rouse us God makes use even of radical and violent rebellion. How can we not feel the urgent need to act when we see young people—sincere in their desire to fight injustice, but with violent means that only call down violent repression—show such courage in prison and under torture that it is difficult to believe that they are sustained only by materialist ideals. He who has eyes to see and ears to hear must feel challenged: how can we remain mediocre and ineffective when we have our faith to sustain us?

Are we so deaf that we do not hear a loving God warning us that humanity is in danger of committing suicide? Are we so selfish that we do not hear the just God demanding that we do all we can to stop injustice from suffocating the world and driving it to war? Are we so alienated that we can worship God at our ease in luxurious temples, which are often empty in spite of all their liturgical pomp, and fail to see, hear, and serve God where he is present and where he requires our presence, among human beings, the poor, the oppressed, the victims of injustices in which we ourselves are often involved?

It is not difficult to hear God’s call today in the world about us. It is difficult to do more than offer an emotional response, sorrow, and regret. It is even more difficult to give up our comfort, break with old habits, let ourselves be moved by grace and change our life, be converted.

Dem Helder Camara, The Desert is Fertile (1974), pp. 18-19.

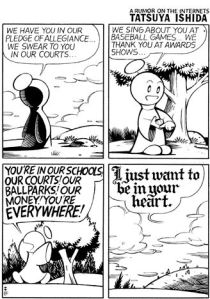

Lack of Christian online civility

Fr. James Martin, S.J. has a very good piece on the abhorrent lack of online civility among many Catholics. Of course, this is an inter-denominational scourge; no church is immune to the problem. I noted in an earlier post that the notion of not bearing false witness seems completely abandoned in cyberspace. Christians evangelizing by example (“preach the Gospel; if necessary use words”) is pitted against the anonymity of the internet – and far too often, the Gospel message of love and respect is ignored, replaced by a quick release of wrath and self-righteousness.

Sermon for Easter Sunday

Resurrection Sunday

St. Mark 18:1-8

This is truly the day that the Lord has made! This is truly the feast of victory for our God! Christ is risen! Indeed, He is risen!

The goal toward which God’s holy Church strove for the forty days of Lent, the goal outlined for us already at the beginning of Advent, has finally been achieved: the triumph of Love and Light over all. Easter is the Feast of feasts and the climax of the Church’s year of grace. It has always been a time when joy and jubilance is unrestrained. Not only literally outside, but also spiritually in our hearts, the sun beams. Our God of Light has beamed into our lives, with warmth, with clarity and with eternal assurance of salvation.

Give thanks, says the apostle, to the Father, who has qualified you to share in the inheritance of the saints in the kingdom of light. He has delivered us from the domain of darkness and transferred us to the kingdom of his beloved Son, in whom we have redemption, the forgiveness of sins. (Col 1:12-13) The dire, fallen and lost state of mankind that we have reflected upon during lent mercilessly and directly to Christ’s death on the cross at Golgotha. Self-righteousness, ambition, hatred and pride led to the murder of Divine Love and the extinguishing of Divine Light. To symbolize the humiliation of Christ, we stripped the altar on Maundy Thursday. To symbolize the death of Christ and the end of his earthly ministry, we closed the Book of Life and performed the Office of Shadows, which is what tenebrae means, for Good Friday. Today we have adorned the church as gloriously and beautifully as we are able—and many thanks to those who have made that possible—because today we celebrate that the Father has delivered us from the domain of darkness and transferred us to the kingdom of his beloved Son, in whom we have redemption.

There could be no greater sign of God’s love and grace than this. In a world of darkness, light triumphs. In a world of hatred and enmity, love is victorious. In a world of death and decay, life itself is crowned with glory. I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep, (John 10:11) Christ told his disciples. Today we reap the undeserved fruits of the selflessness and sacrifice of our good shepherd.

Our Paschal mystery, our Easter mystery has two aspects: by his death, Jesus Christ freed us from sin; and by his resurrection, he opened for us the way to eternal life. These go together, liturgically, theologically and spiritually. You cannot have one without the other; we cannot have the joy of Resurrection Sunday if we did not also have the misery of Good Friday. Every day is Good Friday, every place of Golgotha. Every day is a day of lamenting the state of the world, and every place is the place of Christ’s torment by sin and evil. But this morning we are assured that every day is also Resurrection Day and every place is also the empty tomb—where we know that all the prophecies of Scripture; all that was spoken by God’s holy prophets Isaiah, and Jeremiah and Hosea, Zechariah, and by King David and others—all their words about what lay ahead came true.

This, however, is what is called objective salvation. These are the spiritual realities that are there for us, independent of us. They require a response – subjective salvation. God offers these truths, we have the responsibility to respond, as subjects, as individuals, to that reality. How do we do that?

“For I do not seek to understand in order that I may believe, but I believe in order to understand. For this also I believe-that unless I believe I shall not understand.” This statement by the patron saint of this parish has no greater applicability than when it comes to the death and resurrection of Christ Jesus. I believe in order to understand.

Faith is prior to understanding. Revelation precedes reason. In this day and age, and in the past too, for that matter, religious faith is somehow thought to be unpalatable if it does not conform to reason. We see it in the arguments of those who despise religious faith, but we also see it in many of the arguments of those who claim to defend it. Faith is refashioned so as to appear rational, even scientific. Whether it be the efforts, that have gone on for almost as long as the Church has existed, to conform faith to Greek philosophy, or the more recent attempts to pretend that Biblical narratives are, in fact, 100% literal, chronological history that are threatened by scientific advances—both these involve abandoning the primacy of faith and accepting that faith must conform to some other body of thought in order for it to be true and relevant.

Consider for a moment the three women on whom the Great Dawn of the Resurrection cast its first rays if divine light. They looked at the empty tomb, they were told by the angel that Christ had risen and would fulfill his promises—yet they ran away trembling and afraid. Why? These were devoted followers of Christ, and the life of Christ in almost every single one of its aspects had been prophesied in great detail: The Messiah will be the seed of a woman, we read in Genesis (3:15). He will be born in Bethlehem, said Micah (5:2), by a virgin, according to Isaiah (7:14). Jeremiah (31:15) foretold Herod’s slaughter of the holy innocents, the firstborn, and Hosea (11:1) prophesied that the holy family would flee to Egypt. Zechariah foretold that he would enter Jerusalem on a donkey, and that his betrayal would come at the price of thirty pieces of silver (9:9; 11:12). In Psalms we read how he the Messiah would be accused by false witnesses (27:12), hated without reason (69:4), and that his garments would be divided and they would gamble for his clothing (22:18) We read detailed accounts of how his hands and feet would be pierced (22:16), how he would agonize in thirst (22:15), given gall and vinegar to drink (69:21), how he would be abused, but that none of his bones would be broken (34:20). Zechariah (12:10) tells us how his side would be pierced and that his followers would scatter and desert him (13:7) Isaiah prophesied that he would be crucified with villain (53:12) And all this came to pass.

Consider for a moment the three women on whom the Great Dawn of the Resurrection cast its first rays if divine light. They looked at the empty tomb, they were told by the angel that Christ had risen and would fulfill his promises—yet they ran away trembling and afraid. Why? These were devoted followers of Christ, and the life of Christ in almost every single one of its aspects had been prophesied in great detail: The Messiah will be the seed of a woman, we read in Genesis (3:15). He will be born in Bethlehem, said Micah (5:2), by a virgin, according to Isaiah (7:14). Jeremiah (31:15) foretold Herod’s slaughter of the holy innocents, the firstborn, and Hosea (11:1) prophesied that the holy family would flee to Egypt. Zechariah foretold that he would enter Jerusalem on a donkey, and that his betrayal would come at the price of thirty pieces of silver (9:9; 11:12). In Psalms we read how he the Messiah would be accused by false witnesses (27:12), hated without reason (69:4), and that his garments would be divided and they would gamble for his clothing (22:18) We read detailed accounts of how his hands and feet would be pierced (22:16), how he would agonize in thirst (22:15), given gall and vinegar to drink (69:21), how he would be abused, but that none of his bones would be broken (34:20). Zechariah (12:10) tells us how his side would be pierced and that his followers would scatter and desert him (13:7) Isaiah prophesied that he would be crucified with villain (53:12) And all this came to pass.

Yet as each of these things happened, no one, not one, put the pieces together. No one drew the right conclusions. It would have been easy for the disciples, the followers, these women at the tomb, to employ some logical deduction and, when they arrive at the empty tomb, say “yup, he is risen, Alleluia!” Instead they ran away in fear. They looked at the empty tomb, they were even told by the angel that Christ had risen in fulfillment of his promises—yet they ran away trembling and afraid.

Reason, intellect and the power of deduction are not what reconcile us with our heavenly parent. Faith reconciles, devotion to Jesus reconciles. We know that these women were devoted to Jesus. They mourned his death, and even in the face of the utter disappointment that his death must have been to them, they were devoted to him. They came to honor him. They loved him. Even though they had given up hope and possibly even faith; their immortal savior being dead and all. This devotion and love for a dead activist who claimed immortality and divinity was, frankly, irrational. At the very least, it was confused.

Reason, intellect and the power of deduction are not what reconcile us with our heavenly parent. Faith reconciles, devotion to Jesus reconciles. We know that these women were devoted to Jesus. They mourned his death, and even in the face of the utter disappointment that his death must have been to them, they were devoted to him. They came to honor him. They loved him. Even though they had given up hope and possibly even faith; their immortal savior being dead and all. This devotion and love for a dead activist who claimed immortality and divinity was, frankly, irrational. At the very least, it was confused.

And in the midst of this hazy mixture of love and devotion, something happens: they encounter an angel. We speak of angels often, and in popular culture these rosy-cheeked, winged creatures are thicker than flies. In Scripture, however, angels are actually rare. In St. Matthew’s account, an angel appears to Joseph in a dream and to Jesus as he rejects the temptations of Satan—and then, a third time, to the women at the empty tomb. In Mark, the only living person said to have encountered angels—except the women at the tomb—is St John the Baptist. In Luke, there are a few more: the righteous priest Zacharias, the Blessed Virgin, and the shepherds in the field are visited by an angel. Jesus was strengthened by an angel from heaven as he underwent torment in Gethsemane. And then, as in the other gospel accounts, the women at the empty tomb. In John, the one and only appearance of angels is—you guessed it, at the empty tomb.

Why are they there? Well, what is an angel? There is a lot of theology surrounding this, much of it not very useful, including taxonomies and divisions into categories, their nature and essence, and so forth. The Greek word angelos, just like the Hebrew word malakh, means quite simply a messenger. In both the old and new testaments, those referred to as “messengers” are sometimes human beings, sometimes not. When they are not, they are messengers of God; messengers that communicate God’s truth or offer God’s comfort.

Why are they there? Well, what is an angel? There is a lot of theology surrounding this, much of it not very useful, including taxonomies and divisions into categories, their nature and essence, and so forth. The Greek word angelos, just like the Hebrew word malakh, means quite simply a messenger. In both the old and new testaments, those referred to as “messengers” are sometimes human beings, sometimes not. When they are not, they are messengers of God; messengers that communicate God’s truth or offer God’s comfort.

So let us disregard all the accumulated theology for a moment. As the women, in their devotion, came to the tomb and found it empty, they were met by a messenger of God who proclaimed to them that Christ is risen. This is how we know the truth of our faith—revelation from God. Not logic, not reason, not deduction, not science—but revelation. In Christ, every single prophecy of the Old Testament was fulfilled and completed, yet even his most devoted friends thought he was dead.