Some reflections on SCOTUS, DOMA, and Christian concern

Regardless of where one stands on the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling on the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), the national conversation leading up to, and surrounding this event has been bizarre and confusing. In particular, the permanent avalanche of criticism and concern and outrage from Christians, which has been a staple of the conversation on gay marriage, has now become a bundle of several distinct conversations; conversations that should be separated and kept separate, for reasons of clarity and honesty.

Regardless of where one stands on the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling on the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), the national conversation leading up to, and surrounding this event has been bizarre and confusing. In particular, the permanent avalanche of criticism and concern and outrage from Christians, which has been a staple of the conversation on gay marriage, has now become a bundle of several distinct conversations; conversations that should be separated and kept separate, for reasons of clarity and honesty.

First, the Christian narrative almost always centers on a conversation about the implications of our Scriptural and sacramental views of marriage. This is, of course, as it should. What is the origin, foundation, nature, purpose, and mystical reality of the sacrament of marriage? What can and cannot be permitted by the Church and within the Church? To Christians, such concerns are central. This, however, must first of all be an intra-denominational conversation since not even our churches can agree internally on the how to approach gay marriage (or even marriage in general). No matter how painful it is to admit it, the reality is that there isn’t “a Christian view” of marriage. In most Protestant circles, marriage is not even considered a sacrament, and within and among the churches that do consider it a sacrament, there is nevertheless debate about its symbolic function, civic function, possibility of divorce, whether it extends into life after death, and so on. Differences on gay marriage are nicely illustrated by the positions presented by theologian David J. Dunn and Rev. Andrew Harmon, both belonging to Eastern Orthodoxy. Such differences are also less nicely illustrated by acrimony and splits over gay marriage within several of the so-called mainline Protestant churches.

So the conversation about what marriage is – sacramentally, theologically – is a conversation for Christians, to be conducted first and foremost among Christians. It doesn’t concern, nor should it affect people outside our specific denominations. This does not amount to a retreat from the world, merely an acknowledgement of the reality of diverse Christian perspectives on marriage. After all, a Lutheran view of marriage has no standing, and is not expected to have any standing, among Roman Catholics. An Orthodox view of marriage is not presumed to be acceptable among Presbyterians. We are fine with that. Each denomination knows that its hermeneutic presuppositions are its own and not necessarily those of other Christian denominations. Some of these differences are radical and vast, yet almost no Christian expects other Christians to agree and comply with understandings that are not those of their own denominations. Instead, among ourselves, we simply accept difference and diversity and move on… So what, then, is the reason to demand or expect that our views and presuppositions should have standing elsewhere – such as, for instance, as a source of state or federal law? As a benchmark for what is acceptable in political life? As the rule of life for people who do not share our faith? What makes us think that it is appropriate, or even possible, to set up sacramental theology as a sociopolitical norm for a population as large and diverse as that of the United States?

So the conversation about what marriage is – sacramentally, theologically – is a conversation for Christians, to be conducted first and foremost among Christians. It doesn’t concern, nor should it affect people outside our specific denominations. This does not amount to a retreat from the world, merely an acknowledgement of the reality of diverse Christian perspectives on marriage. After all, a Lutheran view of marriage has no standing, and is not expected to have any standing, among Roman Catholics. An Orthodox view of marriage is not presumed to be acceptable among Presbyterians. We are fine with that. Each denomination knows that its hermeneutic presuppositions are its own and not necessarily those of other Christian denominations. Some of these differences are radical and vast, yet almost no Christian expects other Christians to agree and comply with understandings that are not those of their own denominations. Instead, among ourselves, we simply accept difference and diversity and move on… So what, then, is the reason to demand or expect that our views and presuppositions should have standing elsewhere – such as, for instance, as a source of state or federal law? As a benchmark for what is acceptable in political life? As the rule of life for people who do not share our faith? What makes us think that it is appropriate, or even possible, to set up sacramental theology as a sociopolitical norm for a population as large and diverse as that of the United States?

Marriage matters in the Church for a number of reasons, and all of those reasons are internal to the Church itself; yes, the Church is the Body of Christ, the Life of the World, with a mission in and to the world. Trying to force the world to accept an ontology of sacramental realities as a political baseline is not part of that mission, especially when we Christians ourselves cannot agree on it.

I will participate in a conversation about the sacrament of marriage in an upcoming synod, and then very likely again at another synod in the fall. That’s where such a conversation presently belongs. That’s where it can be expected to be valuable and relevant. In religious convocations. In journals and magazines focusing on faith, theology, spirituality. In sermons and homilies. That is where the issues and arguments can be defined, refined, explained, and understood. Not in the Huffington Post or National Review. Sacramental theology is both too important and too complex to be foisted on people who do not belong to our churches. For their sake and for ours. When a very thoughtful Eastern Orthodox writer, in response to SCOTUS’ DOMA ruling, explains that “marriage is not a “right” but a gift. It is a gift from God, and it comes with certain guidelines and restrictions” then she is certainly correct, but at the same time misses the point that the Republic and its Constitution are simply not in the business of legislating sacraments or divine guidelines. When, for instance, we talk about how marriage is a reflection of Christ being joined to his Church, then this may make perfect sense to us who believe, while at the same time be incomprehensible to outsiders – and utterly irrelevant to legislators. And we should remember: if we do take theology to the market place of secular ideas, using it as a tool of sociopolitical persuasion, we must expect to have it scrutinized, criticized, and even skewered by those who seek a different outcome. Our theology is a framework for understanding and communicating Divine Truth, yet we seem to regularly use it to create political enemies.

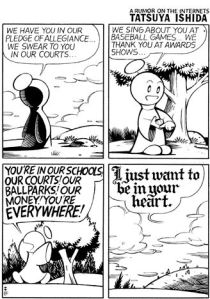

Second, the Christian narrative contains a conversation about the dissipation and disappearance of Christianity from the national culture. “The pews are empty, the youth is sinful, this used to be a Christian country based on Christian values… ” This story about “the end of a Christian nation” seems to automatically engage in the most un-Christian of practices: scapegoating. It ought to bother us that we are so preoccupied with blaming others for the failures of Christians to spread the Gospel and fill the pews… In Christian narratives today, it is almost never our own failure to bear appropriate witness to the God of Love and Mercy that is the root cause of our predicament.. well, we’ve got that going for us…

This “end of a Christian nation” narrative seems to make up the bulk of the conversation about gay marriage, and I have to say, it makes me very uneasy. It makes too many Christians, clergy and laity alike, sound a lot like firebrand theocrats: there seems to be an expectation that our revealed religion has a right to define social, cultural, and political life for everyone in the United States. That our rule of faith must be a political rule of conduct even for those who do not share our faith. That the United States is a Christian country built on Christian principles, so therefore any and all legislation perceived as un-Christian is ipso facto unacceptable (and by definition un-American). We hold these truths to be self-evident, lest the country should tumble even deeper into the bowels of Beelzebub.

The notion that the United States was ever a Christian nation is of course a classic “golden age myth.” Sure, there used to be a higher percentage of confessing Christians in the United States than there are today, so it was only right and proper that legislation reflected this. Such are the basic mechanics of democratic governance. Now the demographics have changed, and since “we the people” are the source of legislation, not Scripture, I don’t know how we object to legislation that reflects these demographic changes. If we do object, it seems to me that we are, in effect, demanding Christian privileges, which in turn means demanding that infidel, heretical, and unchurched compatriots bow to Scripture, rather than the Constitution. Such a demand would seem to be at odds with both the U.S Constitution and Christian Scriptures.

In debates about U.S. politics, the Constitution matters. Legislation does not, and should not cater to the churches and what we may find acceptable or objectionable. Churchmen do not have, nor should have control over the country’s political and legislative processes. Societies are dynamic and ever-changing and the Church is called to preach Christ to a fallen world, not to govern it. I really don’t know what we can do other than to continue to do just that: preach Christ to a fallen world. Proclaim the Good News from the roof tops, engage in works of mercy, lead lives that reflect God’s Love and compassion. We are called to witness, not to coerce. Scripture and Tradition are conduits of Truth, but this Truth must be freely accepted – we don’t get to use them as political weapons.

If SCOTUS’ ruling on DOMA is in fact “un-Christian,” then I have to confess to not being all that shocked and outraged because I have no right to expect Christian legislation. “Always forward, never back,” in the words of Blessed Junipero Serra. We press on, as the Church has done for two millennia. Congress legislates in an un-Christian manner on a regular basis – on issues of war, torture, poverty, health care. For instance, someone would have to explain to me why it is worse for our identity as a Christian country that a gay couple gets to co-sign on a house and visit each other in hospital as next of kin, than that one in six Americans live in poverty, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Is this a Christian state of affairs? Where is the moral outrage, the marches, the petitions, the FB threads, the blog posts? Are homosexuality and abortion the only defining moral issues of our time? We certainly act as if they are. And it makes us look very selective about what Christian morality is and when to enforce it.

Within this “end of a Christan nation” narrative there is a conversation about what is actually happening, and then there is a slippery slope sub-conversation (“if we allow this, then the next thing you know they’ll be marrying live stock and then it is too late for us to do anything about it”). In logic, the slippery slope argument is accurately classified as a fallacy since it doesn’t actually address the issue at hand, but instead deals with imagined future consequences. It is a great tool for squelching just about anything, from Copernican astronomy to the Civil Rights movement, so I generally ignore it. We have to evaluate and judge things with reference to what they actually are, rather than with reference to our own fearful (and more often than not ignorant and profoundly prejudicial) imaginings.

As these two conversations, the sacramental and the sociocultural, co-mingle and mesh into a massive conceptual and analytical mess, there is a third conversation going on. I think this one is the most important, but it is certainly the most marginal: a conversation that links the changing demographics, legislation, and cultural norms and cues, on the one hand, with the Church’s sacramental and counter-cultural understanding, on the other hand. There is a way of participating and witnessing that does not make us look like dead-enders sulking about our loss of sociopolitical power; a way of engaging with the issues in joyful and confident faith in God and genuine love for all our neighbors. It begins with introspection, asking what we can do better. There are real challenges here that we are failing to talk about when instead we elect to screech about modernity and post-modernity’s assault on all that is good and holy.

Pastorally, we are in a changing world that we cannot control. What are the implications of a trend towards increasing social acceptance of gay marriage? Of evolving views on human sexuality and relationships? Making like the ostrich is neither smart, nor constructive. Even in churches that are theologically unable to accept or endorse same sex marriage, there is a desperate need to begin to deal with gay people in a Christian manner. The public debate repeatedly unleashes a level of vitriol, mean-spiritedness, and outright hatred for gay people that is utterly unacceptable among folks who call themselves followers of Christ. The statement that “we hate the sin but not the sinner” has been turned into a rhetorical fig leaf on par with “I’m not a racist, but…” Homophobia and its effects are real pastoral issues, rampant in virtually all our churches. This needs to be a starting point as we move forward. We have to take seriously the spirit and implications of Pope Francis’ recent message: “no one is useless in the Church. We are all needed to build this temple.”

There are other issues also. How do we get beyond the fact that the churches’ loss of power and prestige (which the issue of same sex marriage has made abundantly clear) seems to have created a lot of bitterness and resentment among Christians? Sacramentally, what does it mean for the Church to be the custodian of eternal and unchangeable mysteries in a world that is in constant and ever-more rapid flux. Organizationally and structurally, how are we to deal with culture, society and politics given the fact that the churches are no longer able to dictate the sociocultural game plan? These are real and important questions, but they are rarely discussed because we are too busy trying to pretend that we can achieve sociocultural stasis, even though we know in our heart of hearts that it is impossible. It seems as if we have chosen gay marriage as our battle ground. Well, if we seek to end the dynamism and flux that have defined human affairs since the dawn of time, we will loose. And it won’t be the fault of our gay brothers and sisters, but of our own short sightedness and failure to ask difficult questions of ourselves.

Anders,

Thanks for the first intelligent approach to such issues I have read in a very long time!

Alexis Vinogradov

Fr Alexis, many thanks for your kind words, it means a lot. I hope you and yours are well!

This strikes me as specious. To claim there is no common Christian view of marraige turns on an assumption of strict incommensurability. If that is the route we are to take, then there is no “sacramental” view of marriage either on the very same grounds, nor a definition of what constitutes something as Christian.

While I am unfamiliar with the other author, Dunn is about as representative of Orthodox theology as Bishop Pike or Spong are of Anglicanism.

And while the thesis of a Christian nation was mythological, it wasn’t mythological to believe in inalienable rights that were so because of a foundaitonal in Natural Law. The rejection of inalienable rights seems to be something everyone should be concerned about, but isn’t. All talk of theocracies and the failure of churches seems irrelevant in light of that loss.

Given the relatively small number of homosexuals in the US, there is no new pressing need for churches to deal with homosexuals. There is a pressure machine that increases the pressure for compliance or seeming compliance. The steady increase of say Muslims in the US far outpaces homosexuals for example.

Perry, you have made a few suggestions, let me address them one by one. First, you write that, “To claim there is no common Christian view of marriage turns on an assumption of strict incommensurability.” No, it does not. It turns on the simple and observable fact that doctrines of marriage differ, and in some cases differ vastly, across denominations. And within denominations, concealed by an outward appearance of uniformity, conversations and debates about marriage are taking place. As I said, this is a pretty straightforward empirical observation. Sure, in many aspects there is overlap, but understandings of metaphysical, symbolic, sacramental, legal, and civil aspects of what takes place are not held in common across the board.

The “strict definition of incommensurability” in philosophy, if that’s what you’re referring to, is “the absence of a common standard of measurement or evaluation.” So are you suggesting that my argument turns on there being no common standard of comparing and evaluating various forms of marriage? Well, my claim that there is no common Christian view of marriage doesn’t turn on that assumption, but it does come into play later in the argument. It is in fact a fairly obvious element of the article’s main point.

I believe absolutely, based on Scripture and Sacred Tradition, that we can know what marriage is, why it was instituted, what it involves, and what it ought to look like. I also know for a fact that neither my hermeneutic framework, nor my method, nor my conclusions are acceptable, or even tolerable, to all other Christians – and if we widen the comparative scope to include non-Christians, disagreement increase exponentially.

So yes, I believe in commensurability, that there is an absolute standard for comparison and evaluation. But I also understand that incommensurability is a sociological reality and me wishing it away is not going to make that happen. My standard for evaluation is not necessarily accepted outside my own tradition. And the same goes for the adjectives “sacramental” and “Christian.” Across and between the various denominations, these are terms of contention, not commonality; this is hardly a revolutionary or novel claim.

Given this reality, in a democratic republic, is it the function of the Church (or “the churches”) to coerce others into compliance with legislation that does not accord with their assumptions, frameworks, or wishes? Are we to manage secular society and act as cultural hall monitors? Or is it the Church’s function to provide a witness that attracts people and prompts them to willingly and freely accept our assumptions and standards? To care for orphans and widows in their affliction and to keep ourselves unstained by the world, and thus show the way to God through Christ?

PrTacistus,

That doctrines differ doesn’t imply that they differ absolutely and in every way. That is to say, they do not lack considerable conceptual overlap. Your gloss seems to depend on them not having any. That they do share considerable overlap seems like a simple and observable fact.

Second, there have always been nuances and different ways of glossing marriage and just about everything else. That reasoning would imply that there has never been and is not now anything that can be called the christian church, a christian church let alone the Gospel. That seems absurd.

Third, if you admit of conceptual overlap, then all I need is overlap that picks out some necessary conditions. I think the limitation of marriage to be between males and females, along with some other things seems sufficient to show your claim false. I think Lutherans and Catholics know when and if they agree.

As to strict incommensurability, that is correct and part of what that entails is that there is not any neutral ground or any common ground by which an evaluative standard can be had and employed. Your claim that there is no common Christian view of marriage turns on the thesis that there is no common material necessary and/or sufficient for marriage across the theological schemes. That, as I already demonstrated, seems false. What therefore seems obvious is that your claim is false.

If we take your view as a whole and that no part of it can be shared by any other view, then yes it would follow that there is no common view between Christians. Now, why should we think that is true? I can see no reason to think it is true and lots of reasons why to think it is false.

I do not understand how we get from your claim to knowlegdge conjoined with the fact that others will inevitably disagree with you, to the thesis that the disagreement is absolute and complete? That seems to be what your argument depends on.

You say you believe that there is commensuability in terms of there being an absolute standard for comparison and evalution. But to employ your own reasoning, is there agreement that there is such a standard, what constitutes the standard and how it is to be employed across traditions? Do all Christians agree on this point? If this were vegas, I’d bet no. Consequently I don’t understand your claim of commensurability, since that isn’t a claim of a standard relative to some scheme whereby I can measure other schemes as you seem to be using it. Rather it is a claim about a neutral or common conceptual ground which renders evalution across schemes possible.

Every law entails some moral content and so any body of law compels others who do not agree with the moral content to obey it or suffer the consequences. Do you have a principled reason why we should accept some moral content but exclude others? The quesiton is, where and how is the line to be drawn and on what basis, not if the line is to be drawn.

As to a secular society, I am not clear why we are bound in some absolute fashion to secular ideals. Where is it written that the kingdoms of this world have been ceded y Christ to the Enlightenment? I know not where. Moreover, I think the church can walk and chew gum. That is, it can have degrees of influence. It can be a witness as you suggest as far as ecclesial membership goes, but it can also help sanctify the culture. Why should Christian goodness be restricted to church membership? I forone can’t see why God is a God of redemption but not creation.

It also seems to me that if we aren’t going to be the hall monitors of the culture, someone else will. And I firmly believe they will put us on the short end of the stick. I don’t wish that for my children. As Socrates noted, the worst thing is to be ruled by someone worse than you.

You write that “Dunn is about as representative of Orthodox theology as Bishop Pike or Spong are of Anglicanism.” I simply introduced his piece as a view by an Orthodox theologian in contradistinction to a contrary view by an Orthodox priest. That said, your response – dismissing him as irrelevant rather than dealing with the argument at hand – fails to convince.

Besides, “number of people influenced” is not the metric that matters, but rather “fidelity to the Gospel” – and clearly there is no correlation between the two. The fact that there is a disclaimer added to the article is neither here nor there in terms of how the ideas and concepts he discusses are able to influence, percolate, morph and affect people. It is a common rhetorical maneuver, trying to make opponents’ viewpoints seem marginal, kooky, and weird. Indeed, if we can place them beyond the pale, we are usually able to avoid having to deal with the substance of their arguments. It only takes us so far, though, and it is clearly contrary to genuine dialogue.

I’m afraid I have no idea what inalienable rights according to natural law you are referring to, nor do I understand how they are rejected, by whom, or how.

We have had two centuries in the US of inalienable rights grounded in natural law. These are rights not granted to us by the state or any state but had by us by virtue of what we are. They can be violated and infringed upon but never taken away. As such they are antecedent to the state and the state merely recognizes them. Marriage has been one of those rights. Changing marriage deprives us of our natural right, and grants to the state in principle the power to remove any others and replace them with legal rights, privileges granted by the state so long as they serve the state’s interests. Does that clarify?

No, it does not clarify. I know what natural law is and I know what an inalienable right is, but since neither had anything to do with my argument, I just didn’t get what you were talking about. Besides, the argument seems profoundly flawed. Unless rights are considered a limited good, extending a right to others does not ipso facto deprive you of anything. Unless specific provisions barring you from marriage are made, neither changing the framework within which a right has been instituted, nor changing marriage laws ipso facto deprives you of anything. You write that, “Changing marriage deprives us of our natural right, and grants to the state in principle the power to remove any others and replace them with legal rights, privileges granted by the state so long as they serve the state’s interests.” That sounds fine but falls flat since marriage laws have been changed repeatedly – states banning polygamy, the fed allowing mixed race marriages, and of course individual states banning and later allowing mixed race marriages prior to the 1967 federal decision. With all these changes to marriage, and given that states have had the power to legislate marriage since the nation’s infancy, with the fed muscling in when it wants to, we must all be awfully deprived of our natural rights at this point…

Natural law and natural rights are a terrible basis for arguing about marriage because they are going to open you up to counter attacks about the nature and origins of those natural rights, and suddenly you find yourself debating the existence of homosexual ducks and other nonsense that has nothing to do with what a Christian should argue on the basis of: the Gospel. The state and the fed can legislate all they want, marriage happens before the altar, civil unions happen at city hall – and marriage is not a right, it is a sacrament a therefore a privilege. Tying the importance of marriage to natural rights via civil government mechanisms is not helpful.

You write that “Given the relatively small number of homosexuals in the US, there is no new pressing need for churches to deal with homosexuals.” It is not clear what this is in reference to, it can b one of two things. Either you are responding to my suggestion that homosexuality is becoming increasingly socially acceptable, and that views of human sexuality are evolving. If so, I would just say that it is folly from a pastoral and evangelization perspective to simply ignore such changes, regardless of how many gay folks there are in the country. To stick our heads in the sand and pretend that we are still in the 1950s is a sure-fire way to empty the pews even further. What is lost by thinking critically about issues ahead of time? What virtue lies in always being reactive?

It is also possible (but I would like to think unlikely) that you are responding to my observation that the debate about gay marriage has uncovered, time after time, a hideous and un-Christian combination of fear, loathing and hatred towards gay people from Christians. If so, then your statement that “there is no new pressing need for churches to deal with homosexuals” takes on an very unpleasant character. I am assuming that this is not what you are responding to. I will take this opportunity to restate, however, that the toxicity of regularly expressed “Christian” attitudes to gay people is a multifaceted problem. For the Church, for the spiritual welfare of those who engage in it, and for the gay folks who get slammed with hate speech disguised as “Christian witness.” They are the beloved children of the Almighty, just as you and I. It doesn’t matter if they are 1% or 10% of the population – what matters is how they have been treated.

First, I do not think that there are that many homosexuals as I noted before, relative to the general population. The need, whatever it is, is not pressing. What is pressing is the pressure and propaganda movement for approval. Second, the majority of them aren’t wishing to be members of churches that restrict sexual activity to an celestially sanctioned relationship. It isn’t as if churches changed their stance, the majority of homosexuals would coming tearfully running in. Every time a denomination has done so, the numbers have failed to materialize. I always wonder why that is.

I didn’t say to stick our heads in the sand. Portraying my view in this way is a misrepresentation of what I have said, particularly since it cannot be implied from anything I have written here or elsewhere.

I think what people take to be fear and loathing is very often (though not always) moral repulsion and disgust. I find that perfectly acceptable, as does Scripture, the fathers and the councils. We can toss popes in too just to be ecumenical.

What I have said though is that what is the crucial issue of our time is that of ecclesial discipline, particularly with regard to marriage.

Perry, what implies sticking one’s head in the sand is the statement, now repeated, that the Church has no need to think about new and constructive ways of dealing with homosexuality and homosexuals. Blanket statement: no need, all that is going on around us is pressure and propaganda. That, my friend, is pure myopia.

I guess it saddens me how desperate some folks are for an opportunity to express moral repulsion and disgust towards other folks (in addition to the worrisome levels of fear and loathing). Nobody seems to consults the catechism (St Philaret) any more, which denounces even accurate accusations against neighbors as breaches of the ninth commandments and a cause for repentance. Self-aggrandizement and self-righteousness is rampant. Yes, Perry, ecclesial discipline is sorely needed, but by no means only in relation to marriage

@Perry your last claim is quite misleading. You might as well say the steady increase of Muslims in the US far outpaces women for example. While the Muslim population may be increasing, it makes up less than 1% of the US population, whereas the homosexual population makes up (depending on your source) 5-10% of the population. 5% is one in 20, by no means a small number.

I have no idea where you are getting the 5-10%. The 10% number was from Kinsey which took prison populations as a sample group. Last I checked, homosexuals make up 1.4% of the population via Pew and other research groups. With Bi and Trans, it moves up to 1.6-8%. And last I checked, Muslims tend to have more kids than homosexuals in every way that matters. If we legalize polygamy, their numbers will likely increase further.

Unlike the promise from the title, no mention of either Eriugena or John Duns. :p Though it may be interesting to see an article on Scotus and the Defense of Marriage Act.

Matthew, that cracked me up! I’ll be more careful about Mediaeval philosoper name dropping in the future.

God created man and woman and said no man shall sleep with other as man does sleep with woman. And said do not judge others or you will judged by the same measures. However marriage remains between man and woman and it remains unchanged to end of times, for man and the woman become one by holy matrimony.

And God said do not hate but love one another as you love yourself.

What for Caezar is for Caezar and it is not for and from heaven

And just FYI, here is a disclaimer from the article by Mr. Dunn that you link to.

“Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post belong solely to the author and are not representative of the Orthodox Church.”

Perry, that is a very interesting point. David Dunn’s disclaimer makes it evident that he is not representing Orthodoxy? Why, then, was this not evident when you discussed this article around the time it came out? Why did you utterly ignore that disclaimer when you were trying to accuse Dunn of misrepresenting his views as Orthodox? If we are going to have serious conversations about serious issues, we need to not shift the goal posts around.

* * *

“Perry Robinson says:

June 9, 2012 at 12:58 am

Corneliu,

Dunn and others do not need to pretend to be the official voice of the church to give people the impression through a national news paper that they are representing Orthodox Moral teachng when teaching direclty contrary to it.

Second, he is representing his views not merely on a personal blog, which is one thing, but on a national newspaper. That is a different ball game altogether.

Third, he isn’t expressing his personal opnion, He is expressing what he takes to be and what his readers take to be Orthodox teaching or at the very least what is permissable to believe in Orthodoxy. Neither of which are true. …”

PrTacitus,

Please allow me to direct you to the body of my article that clears away your confusion. I wrote,

“Initially I ignored such postings since they came with a disclaimer that his remarks did not represent the teaching of the Orthodox Church. That seemed to remove any real value from what he had to say. This article lacked that disclaimer. I do not know why. ”

The article you reference with the disclaimer was not the one I was responding directly to. That first article was in the backdrop of my article which was responding to another article that came later. So I did not shift the goal posts. Rather, you didn’t check which article I linked to and was responding to, and failed to notice my remarks in the body of my article. It is an oversight that I am happy to overlook, but in no way did I act in a disingenuous or dishonest manner.

Perry, yes, different article, but no, I actually did read the piece by Dunn to which your blog entry linked. Nonetheless, my bad, I lost track in the comment section. It contained a plethora of sources and imputed offenses,serving to identify the various political, spiritual, and personal maladies that might trouble Dunn (e.g. leftism, liberalism, feminism, being a Pharisee, being destructive, being a trojan horse within Orthodoxy) and others “like him.” It was an interesting read, but I did lose track. Entirely my own fault, so I am most grateful that you are happy to overlook my oversight.

Either way, I guess that my point about Dunn’s disclaimer, restated without the erroneous reference, is simply that it is neither here nor there in the context in which you are now using it, i.e. to show that he is marginal and unrepresentative. Disclaimers show that you do not speak with the authority of your institution, and/or that your institution is not liable for damages resulting from anything that you write. Disclaimers do NOT show that you are marginal within your institution. Every time I write an op-ed, journal article, or book, they need to contain disclaimers – in order to insulate the educational institution at which I teach and/or the church (depending on the subject matter) from any responsibilities and repercussions, not in order to show how marginal I am at my work place. My blog has a disclaimer, your blog (I assume) has a disclaimer; I think their purpose is common knowledge.

That said, while I don’t believe that Dunn is as marginal within grassroots Orthodoxy as you would like him to be, I also don’t believe that he is representative of Orthodoxy at large, nor that his arguments have the imprimatur of your hierarchy. I never claimed that he was mainstream, I merely linked to him as an Orthodox theologian in contradistinction to another orthodox writer. I do think that he is part of a trend that folks need to pay heed to. Beyond simply denouncing him and instructing him to become a repentant sinner “like the rest of us” or else get out of the church (oh, the irony of that argument, in an article denouncing the other as a Pharisee!).

Thank you for a frank, rational and thoughtful post on these issues.

It is quite refreshing!

What I find presumptuous is that freedom of religion doesn’t supersede freedom from religion. If I’m an Agnostic – what gives you the right to bind me by your religious principles??? You want to believe marriage is between a man and a woman, go right ahead. Don’t expect everyone to live by your beliefs.

The principle of life, whether you have faith to know the truth. Are we from this world or not, if we are, you are correct. if not then we have the truth, Jesus called it “I am the road the light and the life”

Multi,

Heterosexual marriage seems like a pre-Xian social institution, not a distinctly Xian act. So agnostics aren’t being bound by some sectarian religious principle.

And besides, all law entails someone’s moral content. Why should anyone be bound by your moral principles?

Perry, in the discussion on Energetic Processions about your “The Pharisees of Sodom” entry, your co-blogger, Monk Patrick, had this to say:

“Fr Patrick (Priest-monk Patrick) says:

June 6, 2012 at 11:29 pm

“… I think that Mr Dunn could have used a couple of other avenues to defend or at least not oppose Gay marriages. One is that the Church cannot impose moral standards on the world and those it should not interfere in secular laws unless that law directly affects the faithful. This argument may be weak but at least it has some Orthodox grounding in Scripture about not judging those outside the Church and those may at least tailor the nature of an Orthodox response from condemnation of such a law to reasons why such a law would not benefit society or cause legal problems for the faithful.”

I know that this was fully a year ago, but I would be interested in your position. When Monk Patrick wrote this, you did not object (at least I can’t find an objection in the discussion thread). Are you still able to accept his notion that such a non-interference policy and the refusal to judge and coerce those outside the Church is compatible with Orthodoxy? If so, why are you now claiming that it turns on “strict incommensurability”, denies “inalienable rights” and natural law, etc? If you no longer agree with Monk Patrick’s claim that this is compatible with Orthodoxy – what has changed?

PrTacitus,

The blog is a hobby as is blogging in general. My lack of comment on every comment by every commentator should not be construed as though I agreed with it or lacked a reason to disagree. Many times I let the conversation go where it will since one of my purposes is to get people talking about important issues. At other times, I am busy with living my life. So your construal of my position, ” are you still able to accept his notion…” is off since that was never my position. Nothing then has changed.

I think Monkpatrick’s position doesn’t hold up. Here is why. First, secular laws are laws formed from the saeculum, namely from the sphere of what is held in common. There is no secular law then that lacks religious and moral content, which is why there is no non-religious argument for SSM, which is why the President appealed to the NT and his moral views. Even if we take secular to mean non-theistic, that still doesn’t imply that the law doesn’t entail some metaphysical and ethical view of the world. I do not know why the state gets to impose that view, which amounts to a state religion.

Paul’s remark about not judging those outside the Church in 1 Cor 5 I believe is concerning ecclesiastical excommunication, not about moral disapproval. God was quite content to judge the nation’s sexual immorality via the prophets on the basis of the law in their hearts via creation and St. Paul does the same, as do other NT writers. That is, even though the nations lacked the Law of Moses, God still judged them by the same moral content. To think otherwise seems to entail some form of Gnosticism with respect to creation.

So the not judging those outside only goes through if we turn the meaning of the text into something other than can be justified from the text. But if that is to be done, then the text is being used to further a view which must have another basis since it is brought to the text rather than derived from it.

What I mean by strict incommensurability is the idea that there is no conceptual overlap or dependence between Christian traditions or even Christian and non-Christian traditions. Such historically is not the case and there has been plenty of cross pollination to some degree or another. This is just to say that these views are historical. Moreover the article seems to assume that since there is no absolute conceptual isomorphism that there is no common necessary condition or conditions. That seems off too.

Perry, interesting, and fair enough re. Monk Patrick’s position. I simply assumed that, since you regularly intervened in the very lengthy comment section following your piece – a very interesting discussion in its own right – you would have had something to say also about your co-bloggers very clearly stated suggestion, if you had indeed found it un-Orthodox. Apologies.

As for what you write here, you don’t deal with my points directly, nor my questions. Instead you elect to ascribe to me concepts and ideas that you then simply dismiss as “off” without further ado. Well, they’re off because neither “strict incommensurability,” nor “absolute conceptual isomorphism,” nor the implications of acceptance or rejection of either, has anything to do with my article. Not a thing. They seem very much like red herrings.

Your exposition of the prophetic tradition seems to confuse the proclamation of God’s will and judgment to the nations – which is what the prophets did – with the institutionalization of God’s will to force the nations into compliance, which they never did. Following on from that, I do hope that you have noticed that I have not once suggested that the Church should be silent on moral issues, or defer any aspect of its theology to changing social norms. To advance the argument in the article, it is not even necessary to be on any one side of the SSM issue. I have merely pointed out that:

– the churches should not expect to have their different and oftentimes disparate theological assumptions elevated to sources of secular legislation

– divergence of doctrines on marriage within Christianity is an empirically observable fact

– the churches need to preach the Gospel to a fallen world, not seek to rule it.

– our witness should draw people to willingly accept the morals of the church, rather than being forced to do so by means of our (waning) political power

– the churches are not called to be the sociocultural managers of society and the world (the prophetic tradition provides very good illustrations of this, I wish I had thought of it before!)

– for pastoral and evanglization reasons we need to be aware of and work within the world as it really is, rather than insist on some abstraction of reality as we would prefer it to be.

If these points constitute a specious argument, you have yet to show how, my friend. You have taken on none of the points, merely stated that the argument is specious and then referred to, well, specious claims about what my argument assumes and implies.

God’s peace to you.

Prtactius,

I thought I dealt with your points directly. I thought the terms I used and the ideas they expressed pick out the ideas that your argument turns on. I gave reasons why the arguments do so. I can’t see how your simple denial amounts to a reason for thinking otherwise.

Your argument in turn depends on there being no common conception of marriage. I gave reasons for thinking that your assessment is mistaken.

As to the prophetic tradition, I don’t think I misread it. Here is why. God set up rulers to promote virtue and curtail vice, that is, as Paul says, punish evil. Since God judges nations by the moral law, the rulers’ job is in part to defend and impliment that law. (Is there some other Scripture has in mind here by which they are judged?) Consequently, God did take sufficient actions to impose that law. Romans 13, among other texts seems relevant here.

The relevant question is not whether you have said that the church should be silent on moral issues, but whether the church should speak to what the state should or should not do. To give up that territory definately does seem to constitute not only giving the culture over to the enemy, but also to cave into social norms since it is a social “norm” that the church can’t and ought not to speak to such issues.

What the churches should expect is different from what they ought to try to accomplish. I can’t see how the former is relevant or significant.

There is divergence, but also convergence. There is no absolute difference. Otherwise what constitutes calling any of them Christian?

Does the preaching of the Gospel entail how law makers, judges and law enforcement should act? Take civil rights for example. Does the Gospel have anything to say about civil rights in the era of Jim Crow or no? If so, on what possible basis do you think it does? Why there and not here? Why with those natural rights, but not these?

I don’t believe I or any other signifnicant opponant of SSM thinks that legilsation will draw people to the church. We do think it restrains evil though and that seems to be the ruler’s job.

The moral influence of the church in legislation doesn’t amount to a managerial position so saying that the church should not be in a managerial position is irrelevant.

I see no reason why we can’t aim for a goal and work within society as it is. Otherwise, why work within society at all and not just focus on the Gospel preaching? Walk, chew gum, got it.

Perry, you continue to ascribe to me views that I don’t have and that miss the point of my argument in ways that seem very odd for such an astute thinker as yourself. Red herrings don’t acquire weight in an argument just because you say so, and they are a repeated feature in the post date July 1, 8:33 pm. Your latest post is merely a repetition of that one, so let me deal with the arguments one by one.

First, I have never claimed that Christian views on marriage “differ absolutely and in every way,” but in fact I stated the opposite.

Second, I have not denied that “there have always been nuances and different ways of glossing marriage.” Also, I have never suggested that “there has never been and is not now anything that can be called the christian church” etc. You are right, such a claim would be absurd – which is why I have never made it.

Third, this is a more substantial point, but it still misses the mark. You write that, “if you admit of conceptual overlap, then all I need is overlap that picks out some necessary conditions. I think the limitation of marriage to be between males and females, along with some other things seems sufficient to show your claim false. I think Lutherans and Catholics know when and if they agree.” As I noted above, I have explicitly stated that there is overlap, but that overlap does not make for sameness. Your ability to pick out common denominators does not make for “a Christian view of marriage” any more than your ability to show common features in your children make them into one child. Unless you are prepared to reduce your definition of marriage to some common denominator that is so far removed from the sacramental reality of Holy Matrimony so as to be unrecognizable. I am not willing to go there. Just because I agree with Pentecostals that marriage is between a man and a woman, that in no way means that I have the same view of marriage as them. And when I officiate at a wedding, I have a very precisely defined understanding of what I am doing and not doing that cannot be abstracted into some notion of commonly shared spare parts.

Fourth, my claim that there is no common Christian view of marriage still does not turn “on the thesis that there is no common material necessary and/or sufficient for marriage across the theological schemes.” You go on to write: “That, as I already demonstrated, seems false. What therefore seems obvious is that your claim is false.” To which I would say that, since I never held this view, your disproving it really has no bearing on the issue. I think you have an unrealistic, perhaps rather scholastic fondness for absolutes, but I’ll try this again:

common elements within different views ≠ one view

several views ≠ zero commonalities

Fifth, you write that “I do not understand how we get from your claim to knowledge conjoined with the fact that others will inevitably disagree with you, to the thesis that the disagreement is absolute and complete? That seems to be what your argument depends on.” Yet again, I have never made that claim, I have been specific about believing the exact opposite, and my argument in no way depends on this notion. As I just noted,

common elements within different views ≠ one view

several views ≠ zero commonalities

Sixth, your discussion about commensurability is rather confusing, but yet again you ascribe assumptions to me that are not mine; about arguing for a “neutral or common conceptual ground which renders evalution across schemes possible.” In fact, I am claiming the exact opposite.

Seventh, you write that “I am not clear why we are bound in some absolute fashion to secular ideals.” Funny, Perry, because neither am I, which is of course why I have never claimed that we are thus bound. You continue, “Where is it written that the kingdoms of this world have been ceded by Christ to the Enlightenment? I know not where.” Me neither, Perry. That said, the kingdom of Christ not being of this world, and this world being the principality of the enemy, should give us a hint as to the direction we are to take.

You write that “I think the church can walk and chew gum. That is, it can have degrees of influence. It can be a witness as you suggest as far as ecclesial membership goes, but it can also help sanctify the culture.” First, I would ask you to show me where we are called to sanctify culture? For instance, Paul never tells the Romans to sanctify culture, he tells them to pay their taxes and quit rocking the boat. Second, I would ask you how we sanctify culture by these culture wars in which we have involved ourselves. Sanctification dedicates something to God – is that what we’re doing? Jockeying here and there for pieces of legislation seems to have nothing to do with sanctification.

You ask, “Why should Christian goodness be restricted to church membership? I for one can’t see why God is a God of redemption but not creation.” Christian goodness is obviously not restricted to Church membership, and clearly God is the God of all of creation. When we follow Christ in the footsteps of the apostles, we are following examples, paragons who how to make that divine goodness manifest to the nations and in creation at large; by ministering and serving, not by imposing and coercing.

“It also seems to me that if we aren’t going to be the hall monitors of the culture, someone else will. And I firmly believe they will put us on the short end of the stick. I don’t wish that for my children.” Me neither, Perry, but Christ promised us hardship, suffering, persecution, and despair. He promised us that they would put us out of the synagogues and kill us. Countless Christians have paid that price, and continue to do so today. Christ never once suggested that following him was a good idea if we wanted a comfortable life and a nice retirement plan. We are seeing this reality all around the world. So, sure, someone else is going to be the hall monitor if we don’t do it. Christ has already told us about that. The question seems to be if we try to find some clever way around what he has told us, or if we leap in and embrace it.

Perry, there were two new items in your latest post that had not already been articulated in the 8:33pm post.

First, your response on the prophetic tradition. I like it, it makes good sense. It doesn’t convince me that my suggested reading is wrong, but I will certainly accept it as an alternative reading.

Second, you wrote that “The relevant question is… whether the church should speak to what the state should or should not do. To give up that territory definately does seem to constitute not only giving the culture over to the enemy, but also to cave into social norms since it is a social “norm” that the church can’t and ought not to speak to such issues.”

Look, I had stated in the original article that the Church has a counter-cultural role. I did not develop the notion, but counter-cultural is not a difficult word. It means, at a minimum, that one does not take norms and cues from the prevailing culture, but challenges them. There could be other stronger definitions, but whatever those are, they suggest the exact opposite of “caving into social norms.” The counter-cultural characteristic of God’s people – of those who have been truly committed to walk with Him even in times when the Israelites and their leaders forgot about God and focused on their own awesomeness (their culture) – is present in the Torah onwards. I have never claimed that this inheritance should be abandoned.

Perry, you say that my simple denials of your claims about what I think do not give you reason to think that I am right… in my claims about what I think… That is, you believe that your concepts and models of what I am arguing somehow override what is actually involved in the construction of my argument. Even if I were to accept this, the reality is that my denials are simple because your concepts are more often than not taken out of thin air. I don’t want to spend time on explaining the various ways in which I don’t hold views that I have never articulated. Red herrings.

I gave you a bullet point list of the main items in my argument, and you haven’t opposed any of them other than by claiming (spuriously) that they hinge on some other abstract notion, and then you go on to disprove the abstraction and then claim that you have disproved my argument. Perry, you are clearly a competent philosopher, and philosophy is a significant part of my formal academic training (mostly in moral philosophy). But the issues at hand here are, from my vantage point. urgent practical pastoral problems. Souls are hurting, people are killing themselves spiritually, and we need ways to address what is going on. That’s where my interest lies.